Setting and Measuring Goals

With a strong emphasis on machine learning, many projects focus on optimizing ML models for accuracy. However, when building software products, the machine-learning components contribute to the larger goal of the system. To build products successfully, it is important to understand and align the goals of the entire system and the goals of the model within the system, as well as the goals of users of the system and the goals of the organization building the system. In addition, ideally, we define goals in measurable terms, so that we can assess whether we achieve the goals or at least make progress toward them. In this chapter, we will discuss how to set goals at different levels and discuss how to define and evaluate measures.

Scenario: Self-help legal chatbot

Consider a business offering marketing services to attorneys and law firms. Specifically, the business provides tools that customers can integrate into their websites to attract clients. The business has long offered traditional marketing services, such as social media campaigns, question-and-answer sites, and traffic analysis, but now it plans to develop a modern chatbot where potential clients can ask questions over a text chat. The chatbot may provide initial pointers to the potential clients’ legal problems, such as finding forms for filing for a divorce and answering questions about child custody rules. The chatbot may answer some questions directly and will otherwise ask for contact information, and possibly relevant case information, to connect the potential client with an attorney. The chatbot can also directly schedule a meeting. The business previously already created a chat feature with human operators, but this was expensive to operate. Rather than old-fashioned structured chatbots that follow a script of preconfigured text choices, the new chatbot should be modern, using a knowledge base and language models to understand and answer the clients’ questions.

Rather than developing the technology from scratch, the small engineering team decides to use one of the many available commercial frameworks for chatbots. The team has a good amount of training data from the old chat service with human operators. At a technical level, the chatbot needs to understand what users talk about and guide conversations with follow-up questions and answers.

Example of a chatbot trying to engage with a user. [Online-only figure.]

Setting Goals

Setting clear and understandable goals helps frame a project's direction and brings all team members working on different parts of the project together under a shared vision. In many projects, goals can be implicit or unclear, so some members might focus only on their local subproblem, such as optimizing the accuracy of a model, without considering the broader context. When ideas for products emerge from new machine-learning innovations, such as looking for new applications of chatbots, there is a risk that the team may get carried away by the excitement about the technology. They may focus on the technology and never step back to think about the goals of the product they are building around the model.

Technically, goals are prescriptive statements about intent. Usually achieving goals requires the cooperation of multiple agents, where agents could be humans, various hardware components, and existing and new software components. Goals are usually general enough to be understood by a wide range of stakeholders, including the team members responsible for different components, but also customers, regulators, and other interested parties. It is this interconnected nature of goals that makes setting and communicating goals important to achieve the right outcome and coordinate the various actors in a meaningful way.

Establishing high-level project goals is usually one of the first steps in eliciting the requirements for the system. Goals may be revisited regularly as requirements are collected, solutions are designed, or the system is observed in production. Goals are also useful for the design process: when decomposing a system and assigning responsibilities to components, we can identify component goals and ensure they align with the overall system goals. In addition, goals often provide a rationale for specific technical requirements and for design decisions. Goals also provide guidance on how to measure the success of the system. For example, communicating clear goals of the self-help legal chatbot—appearing modern and generating leads for customers rather than providing comprehensive legal advice—to the data scientist working on a model will provide context about what model capabilities and qualities are important and how they support the system’s users and the organization developing the system.

Layering Goals

Goals can be discussed at many layers, and untangling different goals can help to understand the purpose of a system better. When asked what the goal of a software product is, developers often give answers in terms of services their software offers its users, usually supporting users doing some task or automating some tasks. For example, our legal chatbot tries to answer legal questions. When zooming out though, much software is built with the business goal of making money, now or later, whether through licenses, subscriptions, or advertisement. In our example, the legal chatbot is licensed to attorneys, and the attorneys hope to attract clients.

To untangle different goals, it is useful to question goals at different layers and to discuss how different goals relate to each other.

Organizational goals. The most general goals are usually at the organizational level of the organization building the software system. Aside from nonprofits, organizational goals almost always relate to money: revenue, profit, or stock price. Nonprofit organizations often have clear goals as part of their charter, such as increasing animal welfare, reducing CO2 emissions, and curing diseases. The company in our chatbot scenario is a for-profit enterprise pursuing short-term or long-term profits by licensing marketing services.

Since organizational objectives are often high-level and pursue long-term goals that are difficult to measure now, often leading indicators are used as more readily observable proxy measures that are expected to correlate with future organizational success. For example, in the chatbot scenario, the number of attorneys licensing the chatbot is a good proxy for expected quarterly profits, the ratio of new and canceled licenses provides insights into revenue trends, and referrals and customer satisfaction are potential indicators of future trends in license sales. Many organizations frame leading indicators as key performance indicators.

Product goals. When building a product, we usually articulate the goals of the product in terms of concrete outcomes the product should produce. For example, the self-help legal chatbot has the goals of promoting individual attorneys by providing modern and helpful web pages and helping attorneys connect with potential clients, but also just the practical goal of helping potential clients quickly and easily with simple legal questions. Product goals describe what the product tries to achieve regarding behavior or quality.

User goals. Users typically use a software product with a specific goal. In many cases, we have multiple different kinds of users with different goals. In our scenario, on the one hand, attorneys are our customers who license the chatbot to attract new clients. On the other hand, the attorneys’ clients asking legal questions are users too, who hope to get legal advice. We can attempt to measure how well the product serves its users in many ways, such as by counting the number of leads generated for attorneys or counting how many clients indicate that they got their question answered sufficiently by the bot. We can also explore users' goals with regard to specific product features, for example, to what degree the chatbot is effective at automatically creating the paperwork for a neighborhood dispute in small-claims court.

In addition to users who directly interact with the product, there are often also people who are indirectly affected by the product or who have expectations of the product. In our chatbot example, this might include judges and defendants who may face arguments supported by increased use of legal chatbots, but also regulators or professional organizations who might be concerned about who can give legal advice or competition. Understanding the goals of indirectly affected people will also help us when eliciting more detailed requirements for the product, as we will discuss in the next chapter.

Model goals. From the perspective of a machine-learned model, the goal is almost always to optimize some notion of accuracy of predictions. Model quality can be measured offline with test data and approximated in production with telemetry, as we will discuss at length in chapters Model Quality and Testing in Production. In our chatbot scenario, we may try to measure to what degree our natural-language-processing components correctly understand a client’s question and answer it sensibly.

Relationships between Goals

Goals at the different levels are usually not independent. Satisfied users tend to be returning customers and might recommend our product to others and thus help with profits. If product and user goals align, then a product that better meets its goals makes users happier, and users may be more willing to cooperate with the product (e.g., react to prompts). Better models hopefully make our users happier or contribute in various ways to making the product achieve its goals. In our chatbot scenario, we hope that better natural-language models lead to a better chat experience, making more potential clients interact with the chatbot, leading to more clients connecting with attorneys, making the attorneys happy, who then renew their licenses, and so forth.

Different kinds of goals often support each other, but they do not always align. Different users may have different goals.

Unfortunately, user goals, model goals, product goals, and organizational goals do not always align. In chapter From Models to Systems, we have already seen an example of such a conflict from a hotel booking service, where improved models in many experiments did not translate into improved hotel bookings (the leading indicator for the organization’s goal). In the chatbot example, this potential conflict is even more obvious: more advanced natural-language capabilities and legal knowledge of the model may lead to more legal questions that can be answered without involving an attorney, making clients seeking legal advice happy, but potentially reducing the attorneys’ satisfaction with the chatbot as fewer clients contract their services. For the chatbot, it may be perfectly satisfactory to provide only basic capabilities, without having to accurately handle corner cases—it is acceptable to fail (and may even be intentional) to then indicate that the question is too complicated for self-help, connecting the client to the attorney. In many cases like this, a good enough model may just be good enough for the organizational goals, product goals, and some user goals.

To understand alignment and conflicts, it is usually a good idea to clearly identify goals at all levels and understand how they relate to each other. It is particularly important to contextualize the product and model goals in the context of the goals of the organization and the various users. Balancing conflicting goals may require some deliberation and negotiation that are normal during requirements engineering, as we will explore in the next chapter. Identifying these conflicts in the first place is valuable because it fosters deliberation and enables designs toward their resolution.

From Goals to Requirements

Goals are high-level requirements from which often more low-level requirements are derived. To understand the requirements of a software product, understanding the goals for the product and the goals of its creators and users is an important early step.

Stepping back, goals can help identify opportunities for machine learning in an organization. Understanding the goals of an organization and the goals of individuals within it, we can (a) explore the decisions that people routinely make within the organization to further their goals, (b) ask which of those decisions could be supported by predictions, and (c) which of those predictions can be supported with machine learning. For example, we can collect user stories in the form of “As [role], I need to make [decision] to achieve [goal]” and “As [role], I need to know [question] to make [decision].” That is, goals are an excellent bridge to explore the business case of machine learning (see previous chapter When to use Machine Learning) and what kind of models and software products to prioritize and whether to support humans with predictions or fully automate some tasks.

Many decisions are routinely made in support of a goal. Typically information is needed to support those decisions, which can be phrased as questions. Some of that information can be provided by predictions from models.

Requirements engineers have pushed the analysis of goals far beyond what we can describe here. For example, there are several notations for goal modeling, to describe goals (at different levels and of different importance) and their relationships (various forms of support and conflict and alternatives), and there are formal processes of goal refinement that explicitly relate goals to each other, down to fine-grained requirements. As another example, the connection from goals to questions and predictions has been formalized in the conceptual modeling notation GR4ML. Requirements-engineering experts can be valuable, especially in the early stages of a project, to identify, align, and document goals and requirements.

Measurement in a Nutshell

Goals can be effective controls to steer a project if they are measurable. Measuring goal achievement allows us to assess project success overall, but it also enables more granular analysis. For example, it allows us to quantify to what extent new functionality by a machine-learning component contributes to our organizational goals, product goals, or user goals.

Measurement is important not only for evaluating goals, but also for all kinds of activities throughout the entire development process. We will discuss measurement in the context of many topics throughout this book, including evaluating and trading off quality requirements during design (chapter Quality Attributes of ML Components), evaluating model accuracy (chapter Model Quality), monitoring system quality (chapter Testing and Experimenting in Production), and assessing fairness (chapter Fairness). Given the importance of measurement, we will briefly dive deeper into designing measures, avoiding common pitfalls, and evaluating measures for the remainder of this chapter.

Everything is Measurable

In its simplest form, measurement is simply the assignment of numbers to attributes of objects or events by some rule. More practically, we perform measurements to learn something about objects or events with the intention of making some decision. Hence, Douglas Hubbard defines measurement in his book How to Measure Anything as “a quantitatively expressed reduction of uncertainty based on one or more observations.”

Hubbard makes the argument that everything that we care about enough to consider in decisions is measurable in some form, even if it is generally considered “intangible.” The argument essentially goes: (1) If we care about a property, then it must be detectable. This includes properties like quality, risk, and security, because we care about achieving some outcomes over others. (2) If it is detectable at all, even just partially, then there must be some way of distinguishing better from worse, hence we can assign numbers. These numbers are not always precise, but they give us additional information to reduce our uncertainty, which helps us make better decisions.

While everything may be measurable in principle, a measurement may not be economical if the cost of measurement outweighs the benefits of reduced uncertainty in decision-making. Typically, we can invest more effort into getting better measures. For example, when deciding which candidate to hire to develop the chatbot, we can (1) rely on easy-to-collect information such as college grades or a list of past jobs, (2) invest more effort by asking experts to judge examples of their past work, (3) ask candidates to solve some nontrivial sample tasks, possibly over extended observation periods, or (4) even hire multiple candidates for an extended try-out period. These approaches are increasingly accurate, but also increasingly expensive. In the end, how much to invest in measurement depends on the payoff expected from making better decisions. For example, making better hiring decisions can have substantial benefits, hence we might invest more in evaluating candidates than we would when measuring restaurant quality for deciding on a place for dinner.

In software engineering and data science, measurement is pervasive to support decision-making. For example, when deciding which project to fund, we might measure each project’s risk and potential; when deciding when to stop testing, we might measure how much code we have covered already; when deciding which model is better, we measure prediction accuracy.

On terminology. Quantification is the process of turning observations into numbers—it underlies all measurement. A measure and a metric refer to a method or standard format of measuring something, such as the false-positive rate of a classifier or the number of lines of code written per week. The terms measure and metric are often used interchangeably, though some authors make distinctions, such as metrics being derived from multiple measures or metrics being standardized measures. Finally, operationalization refers to turning raw observations into numbers for a measure, for example, how to determine a classifier’s false-positive rate from log files or how to gather the changed and added lines per developer from a version control system.

Defining Measures

For many tasks, well-accepted measures already exist, such as measuring precision and recall of a classifier, measuring network latency, and measuring company profits. However, it is equally common to define custom measures or custom ways of operationalizing measures for a project. For example, we could create a custom measure for the number of client requests that the chatbot answered satisfactorily by analyzing the interactions. Similarly, we could operationalize a measure of customer satisfaction among attorneys with data from a survey. Beyond goal setting, we will particularly see the need to become creative with creating measures when evaluating models in production, as we will discuss in chapter Testing and Experimenting in Production.

Stating measures precisely. In general, it is a good practice to describe measures precisely to avoid ambiguity. This is important for goal setting and especially for communicating assumptions and guarantees across teams, such as communicating the quality of a model to the team that integrates the model into the product. As a rule of thumb, imagine a dispute where a developer needs to argue in front of a judge that they achieved a certain goal for the measure, possibly providing evidence where an independent party reimplements and evaluates the measure—the developer needs the description of the measure to be precise enough to have reasonable confidence in these settings. For example, instead of “measure accuracy,” specify “measure accuracy with MAPE,” which refers to a well-defined existing measure (see chapter Model Quality); instead of “measure execution time,” specify “average and 90%-quantile response time for the chatbot’s REST-API under normal load,” which describes the conditions or experimental protocols under which the measure is collected.

Measurement. Once we have captured what we intend to measure, we still need to describe how we actually conduct the measurement. To do this, we need to collect data and derive a value according to our measure from that data. Typically, actual measurement requires three ingredients:

-

Measure: A description of the measure we try to capture.

-

Data collection: A description of what data is collected and how.

-

Operationalization: A mechanism of computing the measure from the data.

Let us consider some examples:

-

Measure: “customer satisfaction of subscribing attorneys” (user goal). Data collection: Each month, we email five percent of the attorneys (randomly selected) a link to an online satisfaction survey where they can select a 1 to 5 stars rating and provide feedback in an open-ended text field. Operationalization: We could simply average the star ratings received from the survey in each month.

-

Measure: “monthly revenue” (organizational goal). Data collection: Attorneys subscribing to the service are already tracked in the license database. Operationalization: Sum of all subscription fees of active subscriptions.

-

Measure: “90%-quantile response latency of the chatbot” (component quality). Data collection: Log the time of each request and each response in a log file on the server. Operationalization: Derive the response latency of each request as the delta between request and response time. Select the fastest 90 percent of the requests in the last 24 hours and report the slowest latency among them.

-

Measure: “branch coverage of the test suite” (software quality). Data collection: Execute the test suite while collecting branch coverage with the coverage.py tool. Operationalization: Measurement implemented in coverage.py, report the sum of branches and the sum of covered branches across all source files in folder src/main.

In all examples, data collection and operationalization are explained with sufficient detail to reproduce the measure independently. In some cases, data collection and operationalization are simple and obvious: It may not be necessary to describe where subscriptions are recorded or how the 90 percent quantile is computed. When standard tools already operationalize the measure, as in the coverage example, pointing to them is usually sufficient. Still, it is often worth being explicit about details of the operationalization, for example, what time window to consider or what specific data is collected just for this measure. For custom measures, such as a custom satisfaction survey, a more detailed description is usually warranted.

Descriptions of measures will rarely be perfect and ambiguity-free, but more precise descriptions are better. Using the three-step process of measurement, data collection, and operationalization encourages better descriptions. Relying on well-defined and commonly accepted standard measures where available is a good strategy.

Composing measures. Measures are often composed of other measures. Especially higher-level measures such as product quality, user satisfaction, or developer productivity are often multi-faceted and may consider many different observations that may be weighed in different ways. For example, “software maintainability” is notoriously difficult to measure, but it can be broken down into concepts such as “correctability,” “testability,” and “expandability,” for which it is then easier to find more concrete ways of defining measures, such as measuring testability as the amount of effort needed to achieve statement coverage.

Example of developing a measure for code maintainability from lower-level measures. [Online-only figure.]

When developing new measures, especially more complex composed ones, many researchers and practitioners find the Goal-Question-Metric approach useful: first clearly identify the goal behind the measure, then identify questions that can help answer whether the goal is achieved, and finally identify concrete measures that help answer the questions. The approach encourages making stakeholders and context factors explicit by considering how the measure is used. The key benefit of such a structured approach is that it avoids ad hoc measures and avoids focusing only on what is easy to quantify. Instead, it follows a top-down design that starts with a clear definition of the goal of the measure and then maintains a clear mapping of how specific measurement activities gather information that is actually meaningful toward that goal.

Evaluating the Quality of a Measure

It is easy to create new measures and operationalize them, but it is sometimes unclear whether the measure really expresses what we intend to measure and whether produced numbers are meaningful. Especially for custom measures, it may be worthwhile to spend some effort to evaluate the measure.

Accuracy and precision. A useful distinction for reasoning about any measurement process is distinguishing between accuracy and precision (not to be confused with recall and precision in the context of evaluating model quality).

Similar to the accuracy of machine-learning predictions, the accuracy of a measurement process is concerned with how closely measured values (on average) represent the real value we want to represent. For example, the accuracy of our measured chatbot subscriptions is evaluated in terms of how closely it represents the actual number of subscriptions; the accuracy of a user-satisfaction measure is evaluated in terms of how well the measured value represents the actual satisfaction of our users.

In contrast, precision refers to how reliably a measurement process produces the same result (whether correct or not). That is, precision is a representation of measurement noise. For example, if we repeatedly count the number of subscriptions in a database, we will always get precisely the same result, but if we repeatedly ask our users about their satisfaction, we will likely observe some variations in the measured satisfaction.

A visualization of the difference between accuracy and precision, showing for example how multiple results can be very close to each other (precise) but far away from the real expected value in the center (inaccurate).

In measurement, we need to address inaccuracy and imprecision (noise) quite differently: Imprecision is usually easier to identify and handle, because we can see noise in measurements and can use statistics to handle the noise. Noise will often average out over time—for example, if the model computed some answers to chat messages a bit faster or slower due to random measurement noise, the average response time will be representative of what users observe. Inaccuracy, in contrast, is much more challenging to detect and handle, because it represents a systematic problem in our measures that cannot be detected by statistical means. For example, if we accidentally count expired subscriptions when computing revenue, we will get a perfectly repeatable (precise) measure that always reports too many subscriptions. We will not notice the problem from noise, but possibly only when discrepancies with other observations are noticed. To detect inaccuracy in a data generation process, we must systematically look for problems and biases in the measurement process or somehow have access to the true value to be represented.

Validity. Finally, for new measures, it is worth evaluating measurement validity. As an absolute minimum, the developers of the measure should plot the distribution of observations and manually inspect a sample of results to ensure that they make sense. If a measure is important, validity evaluations can go much further and can follow structured evaluation procedures discussed in the measurement literature. Typically, validity evaluations ask at least three kinds of validity questions. Construct validity: Do we measure what we intend to measure? Does the abstract concept match the specific scales and operationalizations used? Predictive validity: Does the measure have an ability to (partially) explain a quality we care about? Does it provide meaningful information to reduce uncertainty in the decision we want to make? External validity: Does the measure generalize beyond the specific observations with which it was initially developed?

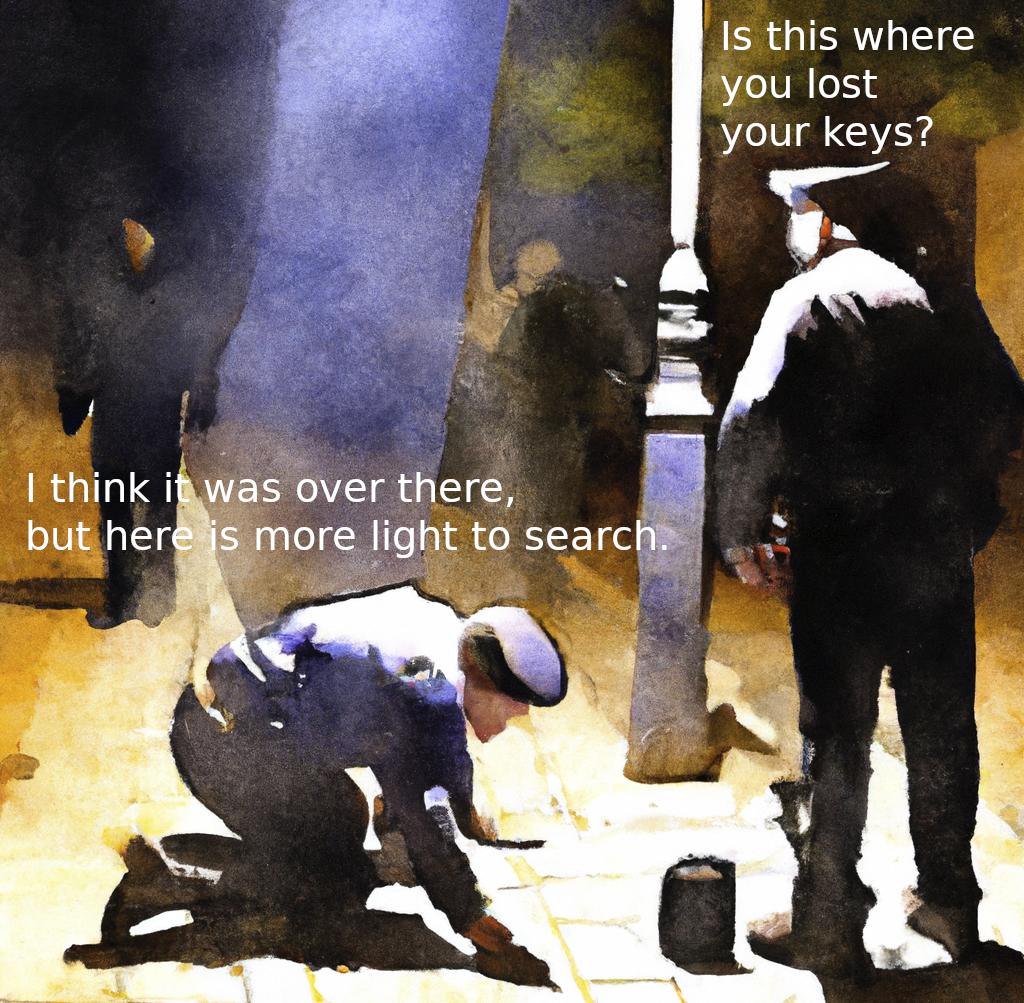

Common Pitfalls

Designing custom measures is difficult and many properties can seem elusive. It is tempting to rely on cheap-to-collect but less reliable proxy measures, such as counting the number of messages clients exchange with the chatbot (easy to measure from logs) as a proxy for clients’ satisfaction with the chatbot. The temptation to use convenient proxies for difficult-to-measure concepts is known as the streetlight effect, a common observational bias. The name originates from the anecdote of a drunkard looking for his keys under a streetlight, rather than where he lost them a block away, because “this is where the light is.” Creating good measures can require some effort and cost, but it may be worth it to enable better decisions than possible with ad hoc measures based on data we already have. Approaches like the Goal-Question-Metric design strategy and critically validating measures can help to overcome the streetlight effect.

Typical illustration of the streetlight effect: Focusing attention on aspects that are easy to observe. [Online-only figure.]

Furthermore, providing incentives based on measures can steer behavior, but they can lead to bad outcomes when the measure only partially aligns with the real goal. For example, it may be a reasonable approximation to measure the number of bugs fixed in software as an indicator of good testing practices, but if developers were rewarded for the number of fixed bugs, they may decide to game the measure by intentionally first introducing and then fixing bugs. Humans and machines are generally good at finding loopholes and optimizing for measures if they set their mind to it. In management, this is known as Goodhart’s law, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” In machine learning, this is discussed as the alignment problem (see also chapter Safety). Setting goals and defining measures can set a team on a joint path and foster communication, but avoid using measures as incentives.

Summary

To design a software product and its machine-learning components, it is a good idea to start with understanding the goals of the system, including the goals of the organization building the system, the goals of users and other stakeholders, and the goals of the ML and non-ML components that contribute to the system goals. In setting goals, providing measures that help us evaluate to what degree goals are met or whether we are progressing toward those goals is important, but it can be challenging.

In general, measurement is important for many activities when building software systems. Even seemingly intangible properties can be measured (to some degree, at some cost) with the right measure. Some measures are standard and broadly accepted, but in many cases we may define, operationalize, and validate our own. Good measures are concrete, accurate, and precise and fit the purpose for which they are designed.

Further Readings

-

An in-depth analysis of the chatbot scenario, which comes from a real project observed in this excellent paper. It discusses the various negotiations of goals and requirements that go into building a product around a nontrivial machine-learning problem: 🗎 Passi, Samir and Phoebe Sengers. “Making data science systems work.” Big Data & Society, 7 no. 2 (2020).

-

A book chapter discussing goal setting for machine-learning components, including the distinction into organizational objectives, leading indicators, users goals, and model properties: 🕮 Hulten, Geoff. Building Intelligent Systems: A Guide to Machine Learning Engineering. Apress, 2018, Chapter 4 (“Defining the Intelligent System’s Goals”).

-

A great textbook on requirements engineering with good coverage of goal-oriented requirements engineering and goal modeling: 🕮 Van Lamsweerde, Axel. Requirements Engineering: From System Goals to UML Models to Software. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

-

A classic text on how measurement is uncertainty reduction for decision-making and how to design measures for seemingly intangible qualities: 🕮 Hubbard, Douglas W. How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

-

An extended example of the GR4ML modeling approach to capture goals, decisions, questions, and opportunities for ML support in organizations: 🗎 Nalchigar, Soroosh, Eric Yu, and Karim Keshavjee. “Modeling Machine Learning Requirements from Three Perspectives: A Case Report from the Healthcare Domain.” Requirements Engineering 26 (2021): 237–254.

-

A concrete example of using goal modeling for developing ML solutions, with extensions to capture uncertainty: 🗎 Ishikawa, Fuyuki, and Yutaka Matsuno. “Evidence-Driven Requirements Engineering for Uncertainty of Machine Learning-Based Systems.” In International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), pp. 346–351. IEEE, 2020.

-

An example of a project where model quality and leading indicators for organizational objectives surprisingly did not align: 🗎 Bernardi, Lucas, Themistoklis Mavridis, and Pablo Estevez. “150 Successful Machine Learning Models: 6 Lessons Learned at Booking.com.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pp. 1743–1751. 2019.

-

A brief introduction to the goal-question-metric approach: 🗎 Basili, Victor R., Gianluigi Caldiera, and H. Dieter Rombach. “The Goal Question Metric Approach.” Encyclopedia of Software Engineering, 1994: 528–532.

-

An in-depth discussion with a running example of validating (software) measures: 🗎 Kaner, Cem and Walter Bond. “Software Engineering Metrics: What Do They Measure and How Do We Know.” In International Software Metrics Symposium, 2004.

-

A popular book covering software metrics in depth: 🕮 Fenton, Norman, and James Bieman. Software Metrics: A Rigorous and Practical Approach. CRC Press, 2014.

-

Two popular science books with excellent discussions of the problematic effects of designing incentives based on measures as extrinsic motivators: 🕮 Pink, Daniel H. Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Penguin, 2011. 🕮 Kohn, Alfie. Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes. HarperOne, 1993.

As all chapters, this text is released under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. Last updated on 2024-06-17.