Data Quality

Data is core to most machine-learning products, and data quality can make or break many projects. Data is used for model training and during inference, and more data is usually collected as telemetry at runtime. Models trained on low-quality data may be performing poorly or may be biased or outdated; user decisions based on predictions from low-quality data may be unreliable, and so may be operating decisions based on low-quality telemetry. Overall, a system that does not attend to data quality may become brittle and will likely degrade over time if it works in the first place.

Data quality is a challenge in many projects. According to various reports, data scientists spend more than half their working time on data cleaning and rarely enjoy that task. Workers who collect, enter, and label data are often separated from those consuming the data and are rarely seen as an integral part of the team. Data is rarely documented or managed well. A data-quality initiative must attend to specific quality requirements and data-quality checks but also holistically consider data-quality management as part of the overall system.

Scenario: Inventory Management

As a running example, consider a smart inventory-management software for supermarkets. The software tracks inventory received and stored, inventory moved from storage to supermarket shelves, and inventory sold and discarded. While experienced employees of the supermarket tend to have a good sense of when and how many products to order, the smart inventory-management system will use machine learning to predict when and how much shall be ordered, such that the supermarket is always sufficiently stocked, while also coping with limited storage capacity and avoiding waste when expired products must be thrown away.

Such a system involves a large amount of data from many different sources. There are thousands of products from different vendors with different shelf lives, different delivery times and modalities, changing consumer behavior, the influence of discounts and other marketing campaigns from the supermarkets as well as those from the vendors, and much more. Yet, such a system is business critical and can significantly impact the supermarket’s profits and their customers' experiences.

For now, let us assume the supermarket already has several databases tracking products (ID, name, weight, size, description, vendor), current stock (mapping products to store locations, tracking quantity and expiration dates), and sales (ID, user ID if available, date and time, products and prices).

Data Quality Challenges

Data quality was a concern long before the popularity of machine learning. Traditional non-ML systems often store and process large amounts of data in databases, often business-critical data. Data quality is multifaceted, and quality needs are specific to individual projects. Decades of research and practical experience with data management and databases have accumulated a wealth of knowledge about defining data quality, evaluating data quality, and data cleaning. Here, we can only scratch the surface.

Quantity and quality of data in machine learning. In machine learning, data influences the quality of the learned models. A machine-learning algorithm needs sufficient data to pick up on important patterns in the data and to reasonably cover the whole target distribution. In general, more data leads to better models. However, this is only true up to a point—usually, there are diminishing effects of adding more and more data.

It is useful to distinguish imprecise data (random noise) from inaccurate data (systematic problem), as we discussed for measurement precision and accuracy more broadly in chapter Setting and Measuring Goals.

Imprecise data from a noisy measurement process may lead to less confident models and occasionally spurious predictions if the model overfits to random measurement noise. However, noise in training data, especially random noise, is something that most machine-learning techniques can handle quite well. Here, having a lot of data helps to identify true patterns as noise gets averaged out.

In contrast to imprecision, inaccurate data is much more dangerous, because it will lead to misleading models that make similarly inaccurate predictions. For example, a model trained on sales data with a miscalibrated scale systematically underrepresenting the sales of bananas will predict a too-low need for ordering bananas. Also note that inaccurate data with systematic biases rather than noisy data is the source of most fairness issues in machine learning (see chapter Fairness), such as recidivism models trained with data from past judicial decisions that were biased systematically (not randomly) against minorities. Here, collecting more data will not lead to better models if all that data has the same systematic quality problem.

For the machine-learning practitioner, this means that both data quantity and data quality are important. Given typically a limited budget, practitioners must trade off costs for acquiring more data with costs for acquiring better data or cleaning data. It is sometimes possible to gain great insights even from low-quality data, but low quality can also lead to completely wrong and biased models, especially if data is systematically biased rather than just noisy.

Data quality criteria. There are many criteria for how to evaluate the quality of data, such as:

-

Accuracy: The data was recorded correctly.

-

Completeness: All relevant data was recorded.

-

Uniqueness: All entries are recorded once.

-

Consistency: The data agrees with each other.

-

Currentness: The data is kept up to date.

Several data-quality models enumerate quality criteria, including ones relating to how data is stored and protected. For example, the ISO/IEC standard 25012 defines fifteen criteria: accessibility, accuracy, availability, completeness, compliance, confidentiality, consistency, credibility, currentness, efficiency, portability, precision, recoverability, traceability, and understandability.

Data-quality problems can manifest for every criterion. For example, in our inventory system, somebody could enter the wrong product or the wrong number of items when a shipment is received (accuracy), could simply forget an item or an entire shipment (completeness), could enter the shipment twice (uniqueness), could enter different prices for the same item in two different tables (consistency), or simply could forget to enter the data until a day later (currentness). Depending on the specific system, quality problems for some criteria may be more important than others.

The myth of raw data. When data represents real-world phenomena, it is always an abstraction. Somebody has made a decision about what data to collect, how to encode the data, and how to organize it for storage and processing. For example, when we record how many bananas are in our inventory, we need to decide whether we record weight, number, or size, whether and how we record ripeness, and whether to record the country of origin, the supplier, or a specific plantation. Even when data is used directly from a sensor, the designer of the sensor has made decisions about how to observe real-world phenomena and encode them. For example, even a barcode scanner in a supermarket had to make decisions about how to process camera inputs and what noise is tolerated to record a number for a barcode on a product. Data collection is always necessarily selective and interpretative. It is never raw and objective. Arguably, “raw data” is an oxymoron. At most, we can consider data as raw with regard to somebody else’s collection decisions.

When we accept that data is never raw and is always influenced by design decisions and interpretations, we can recognize that there is tremendous leverage in defining what data to collect and how to collect data. We can collect data specifically to draw attention to a problem, for example, collecting data about working conditions at banana plantations of our suppliers, but we can equally omit aspects during data collection to protect them from scrutiny. Deciding what data to collect and how can be a deeply political decision. There is a whole research field covering the ethics and politics of data.

Beyond politics, deciding what and how to collect data obviously affects also the cost of data collection and the quality of the collected data with regards to various expectations and requirements. For example, if we want exact producer information about our bananas, we might not be able to work with some wholesalers who do not provide that information; if we want exact weight measurements of each individual banana, the measurement will be very costly as compared to measuring only the overall weight of the shipment.

In the end, the accuracy of data can only be evaluated with regard to a specific operationalization of a measurement process.

Data is noisy. In most real-world systems, including production machine-learning systems, data is noisy, rarely meeting all the quality criteria above. Noise can come from many different sources: (1) When manual data entry is involved, such as a supermarket employee entering received shipments, mistakes are inevitable. Automated data transfer, such as electronic sales records exchanged between vendor and receiver, can reduce the amount of manual data entry and associated noise. (2) Many systems receive data through sensors that interact with the real world and are rarely fully reliable. In our example, sensors-related data-quality problems might include misreading barcodes or problems when scanning shipping documents from crumpled paper. (3) Data created from computations can suffer quality problems when the computations are simply wrong, corrupted from a crash in the system, or inaccurate from model predictions used. For example, a supermarket employee might enter a received delivery a second time if the first attempt crashed with an error message, even though the data had already been written to the database.

Data changes. Data and assumptions we make about data can evolve over time in many ways for many different reasons. In general, mechanisms of how we process data or evaluate data quality today may need to be adapted tomorrow.

First, software, models, and hardware can change over time. Software components that produce data may change during software updates and may change the way the data is stored. For example, our inventory management system might change how weights are encoded internally, throwing off downstream components that read and analyze the data. Similarly, model updates may improve or degrade the quality of produced data used by downstream components. Also, hardware changes over time, as it degrades naturally or is replaced. For example, as sensors age, automatically scanned shipping manifests will contain more unreadable parts.

Second, operator and user behavior can change over time. For example, as cashiers gain experience with the system, they make fewer errors during manual data entry. Shoppers may behave differently in snowstorms or when a discount is offered. Data that used to be an outlier may become part of the typical distribution and vice versa. In addition to natural changes in user behavior, users can also deliberately change their behavior. Predictions of a model can induce behavior changes, affecting distributions of downstream data, for example, when a model suggests lowering the price of an overstocked, soon-to-expire product. Users can also intentionally attempt to deceive the model, such as a vendor buying their own products to simulate demand, as we will discuss in chapter Security and Privacy.

Finally, the environment and system requirements can change, influencing the data-quality requirements for the system. For example, if a theft prediction component is added to the inventory management system, the timeliness of recording missing items may matter much more than without such component; and as the supermarket changes its frequency of inventory checks, our assumptions about the currentness of data may need to be adjusted.

Bad data causes delayed problems. Unfortunately, data-quality problems can take a long time to notice. They are usually very difficult to spot in traditional offline evaluations of prediction accuracy (see chapter Model Quality). For example, a project that trains and evaluates a classifier with outdated data may get promising accuracy results in offline evaluations, but may only notice that the model is inadequate for production use once it is deployed. In general, as studies have confirmed again and again, the later in a project a problem is discovered, the more expensive it is to fix, because we may have already committed to many faulty assumptions in the system design and implementation.

Just evaluating how well a model fits the data provides little information about how useful the model is for a practical problem in the real world and whether it has captured the right phenomena with sufficient fidelity and validity. As a consequence, data quality must be discussed and evaluated early in a project. Building models without understanding data and its quality can be a liability for a project.

Organizational sources of data-quality problems. Data collection and data cleaning work is often disliked by data scientists and often perceived as low-prestige clerical work outsourced to contractors and crowd workers with poor working conditions. A Google study put this observation right in the title: “Everyone Wants to Do the Model Work, Not the Data Work.”

The same study found that data scientists routinely underestimate the messiness of phenomena captured in data and make overly idealistic assumptions, for example, assuming that data will be stable over time. Data scientists also often do not have sufficient domain expertise to really understand nuances in the data, but they nonetheless move quickly to train proof-of-concept models. Finally, documentation for data is often neglected, hindering any deeper understanding across organizational boundaries.

On a positive note, the study also found that most data-quality problems could have been avoided with early interventions. That is, data-quality problems are not inevitable, but data quality can be managed, and a collaborative approach between data producers and data consumers can produce better outcomes.

Data-Quality Checks

There are many different approaches to enforcing consistency on data, detecting potential data-quality problems, and repairing them. The most common approaches check the structure of the data—its schema. Schema enforcement is well known from databases and is usually referred to as data integrity. Checks beyond the schema often look for outliers and violations of common patterns; such checks are usually implemented with machine learning. But before any automated checks, quality assessment usually requires a good understanding of the data, which almost always starts with exploratory data analysis.

Exploratory Data Analysis

Ideally, data generation processes are well documented, and developers already have a good understanding of the data, its schema, its relations, its distributions, its problems, and so forth. In practice, though, we often deal with data acquired from other sources and data that is not fully understood. Before taking steps toward assuring data quality, exploring the data to better understand it is usually a good idea.

Exploratory data analysis is the process of exploring the data, typically with the goal of understanding certain aspects of it. This process often starts with understanding the shape of the data: What data types are used (e.g., images, tables with numeric and string columns)? What are the ranges and distributions of data (e.g., what are typical prices for sales, what are typical expiration dates, how many different kinds of sales taxes are recorded)? What are relationships in the data (e.g., are prices fixed for certain items)? To understand distributions, data scientists usually plot distributions of individual columns (or features) with boxplots, histograms, or density plots and plot multiple columns against each other in scatter plots. Computational notebooks are a well-suited environment for this kind of visual exploration.

In addition, it is often a good idea to explore trends and outliers. This sometimes provides a sense of precision and of typical kinds of mistakes. Sometimes, it is possible to go back to the original data or domain experts to check correctness; for example, does this vendor really charge $10/kg for bananas, or did we really sell four times the normal amount of toilet paper last June in this region?

Beyond visual techniques, a number of statistical analyses and data mining techniques can help to understand relationships in the data, such as correlations and dependencies between columns. For example, the delivery date of an item hopefully correlates with its expiration date, and sales of certain products might associate with certain predominant ethnicities in the supermarkets' neighborhoods. Common techniques here are association rule mining and principal component analysis.

Data Integrity with Data Schemas

A schema describes the expected format or structure of data, which includes the list of expected entries and their types, allowed ranges for values, and constraints among values. For example, we could expect and enforce that data for a received shipment always contains one or more pairs of a product identifier and product quantity, where the product identifier refers to a known product, and the product quantity is expressed as a positive decimal number with one of three expected units of measurement for that quantity (e.g., item count, kg, liter).

Data schemas set hard constraints for the format of data. Schema compliance is not a relative measure of accuracy or fit, but all data is expected to conform strictly to the schema. Conformance of data to an expected schema is also known as data integrity.

Relational database schemas. Schemas are familiar to users of relational databases, where schemas describe the format of tables in terms of which columns they contain and which types of data to expect for each column. A schema can also specify explicitly whether and where missing values (null) are allowed. In addition, relational databases can all enforce some rules about data across multiple rows and tables, in particular, whether data in specific columns should be unique for all rows (primary key), and whether data in specific columns must correspond to existing data in another table (foreign key).

CREATE TABLE Suppliers (

ID INT PRIMARY KEY,

Name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

ContactName VARCHAR(255),

ContactPhone VARCHAR(20)

);

CREATE TABLE Products (

ID INT PRIMARY KEY,

Name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

Category VARCHAR(50),

UnitPrice DECIMAL(10, 2) NOT NULL,

QuantityInStock INT NOT NULL,

Unit VARCHAR(5) NOT NULL CHECK (Unit IN('count', 'kg', 'liter'))

SupplierID INT,

FOREIGN KEY (SupplierID) REFERENCES Suppliers(ID)

);

An example of an SQL statement to create tables with a provided schema. It indicates two tables with a number of columns each and indicates for each column the type of data to expect. For instance, it enforces that a supplier is identified by a numeric ID, that unit needs to have one of three valid values, that a phone number can be provided as any string of up to twenty characters. It also ensures that supplier and product identifiers are unique (primary key) and that a product can only refer to suppliers that exist in the supplier table.

Traditional relational databases require a schema for all data and refuse to accept new data or operations on existing data that violate the constraints in the schema. For example, a relational database would return an error message when inserting a product with an ill-formatted quantity or a supplier identifier already in the database.

Enforcing schemas in schemaless data. In machine-learning contexts, data is often exchanged in schemaless formats, such as text entries in log files, tabular data in CSV files, tree-structured documents (json, XML), and key-value pairs. Such data is regularly communicated through plain text files, through REST APIs, through message brokers, or stored in various (non-relational) databases.

ProductID,Product Name,Quantity,Unit,SupplierID

101,Banana,50,kg,201

102,Cucumber,75.5,kg,502

103,Cauliflower,30,count,283

An example of a list of sales stored as a comma-separated text file with four columns.

Exchanging data without any schema enforcement can be dangerous, as changes to the data format may not be detected easily, and there is no way of communicating expectations on the data format and what constitutes valid and complete data between a data provider and a consumer. In practice, consumers of such unstructured data should validate that the data conforms to expectations.

Many tools have been developed to define schemas and check whether data conforms to schemas for key-value, tabular, and tree-structured data. For example, XML Schema is a well-established approach to limit the kind of structures, values, and relationships in XML documents; similar schema languages have been developed for JSON and CSV files, including JSON Schema and CSV Schema. Many of these languages support checking quite sophisticated constraints for individual elements, for rows, and for the entire dataset.

version 1.1

@totalColumns 5

id: positiveInteger

name: length(1,255)

quantity: numericLiteral

unit: is("count") or is("kg") or is("liter")

supplierId: positiveInteger

Example of a schema specification for a CSV file in CSV Schema that ensures value types.

In addition to using schema languages, schemas can also be checked in custom code, simply validating data after loading. For data in data frames, the Python library Great Expectations is popular for writing schema-style checks.

expect_column_values_to_be_of_type("id", "int")

expect_column_values_to_be_unique("id")

expect_column_values_to_be_of_type("quantity", "float")

expect_column_values_to_be_between("quantity", min_value=0, max_value=None)

expect_column_values_to_be_in_set("unit", ["count", "kg", "liter"])

expect_column_values_to_be_of_type("supplierId", "int")

An example of checks with Great Expectations to enforce a schema.

A side benefit of many schema languages is that they also support efficient data encoding for storage and transport in a binary format, similar to internal storage in relational databases. For example, numbers can be serialized compactly in binary format rather than written as text, and field names can be omitted for structured data. Many modern libraries combine data schema enforcement and efficient data serialization, such as Google's Protocol Buffers, Apache Avro, and Apache Parquet. In addition, many of these libraries provide bindings for programming languages to easily read and write structured data, exchange it between programs in different languages, all while assuring conformance to a schema. Most of them also provide explicit versioning of schemas that ensure that changes to the schema on which producers and consumers rely will be detected automatically.

Inferring the schema. Developers usually do not like to write schemas and often enjoy the flexibility of schemaless formats and NoSQL databases, where data is flexibly stored in key-value or tree structures (e.g., JSON). To encourage the adoption of schemas, it is possible to infer likely schemas from sample data.

In a nutshell, tools like TFX use some form of search or synthesis to identify a schema that captures all provided data. For example, a tool might detect that all entries in the first column of a data frame are unique numbers, all entries in the second column are text, all entries in the third column are numbers with up to two decimals, and in the fourth column we only observe the two distinct values “count” and “kg.” More complicated constraints across multiple columns can be detected with specification mining, rule mining, or schema mining techniques. While inference may not be precise (especially if the data is already noisy and contains mistakes), it may be much easier to convince developers to refine an inferred schema than to ask them to write one from scratch.

Repair. A schema can detect when data does not have the expected format. How to handle or repair ill-formatted data depends on the role of the data in the application. End users can be informed about the formatting problem and asked to manually repair the inputs, like the validation mechanisms in a web form. Ill-formatted data can also simply be dropped or collected in a file for later manual inspection. Finally, also automated repair is possible, such as replacing missing or ill-formatted values with defaults or average values. For example, if a scanned order form states “12.p kg” of bananas, we could automatically convert this to 12 kg as the nearest valid value. This form of programmatic data cleaning across entire datasets is common in data science projects.

Wrong and Inconsistent Data

While enforcement of a schema is well established, it focuses only on the format and internal consistency of the data. Quality issues beyond what a schema can enforce are diverse and usually much more difficult to detect. There is no approach that can generally detect whether data accurately represents a real-world phenomena. Most approaches here identify suspicious data that might indicate a problem, rather than identifying a clear violation of some property—they check plausibility rather than correctness or accuracy. This is the realm of checking data distributions, of detecting outliers and anomalies, and of using domain-specific rules to check data.

Anomaly detection is a well-studied approach that learns common distributions of data and identifies when data is an unusual outlier. For example, anomaly detection can identify that a shipment of 80,000 kg of bananas is unlikely when usual sales rarely exceed 2,000 kg per week. Basic anomaly detection is straightforward by learning distributions for data, but more sophisticated approaches analyze dependencies within the data, time series, and much more. For example, we might learn seasonal trends for cherry sales and detect outliers only with regard to the current season. We can also detect inconsistencies between product identifiers and product names that deviate from past patterns. Detected outliers are usually not easy to repair automatically, but can be flagged for human review or can be removed or deprioritized from training data. Expected distributions are rarely written manually, though it is possible (e.g., Great Expectations' expect_column_kl_divergence_to_be_less_than). In most cases, distributions are learned, and detection approaches are subsequently tuned to detect useful problems without reporting an overwhelming amount of false positives.

When data has redundancies, it can be used to check consistency. For example, we would expect the weight stated on a scanned delivery receipt to match that recorded from a scale or even from sales data. In many settings, the same data is collected in multiple different ways, with different sensors, such as using both LiDAR and camera inputs for obstacle detection in an autonomous train.

Where domain knowledge is available, it can be integrated into consistency checks. For example, we can check that the amount of bananas sold does not exceed the amount of bananas bought—using our knowledge about the relationship of these values in the real world. Similarly, it is common to use zip and address data to check address data for plausibility, identifying mistyped zip codes, street names, and city names from inconsistencies among those. Spell checkers perform a similar role. The domain data can be provided as an external knowledge base or learned from existing data.

Many approaches also specifically look for duplicates or near duplicates in the data. For example, an approach could flag if two identical shipments are received on the same day, differing only in their identifier.

Finally, it is possible to learn to detect problems from past repairs. We could observe past corrections done manually in a database, such as observing when somebody corrected the weight of a received item from the value originally identified from the scanned receipt. Also, active-learning strategies can be used to guide humans to review select data that provides more insights about common problem patterns.

Repair. At a low volume, detected problems can be flagged for human review, but also automated forms of data cleaning for outliers and suspicious data are common in data science. If a model detects an inconsistency with high enough confidence, it can often suggest a plausible alternative value that could be used for repair. For example, a tool might identify an inconsistency between product identifier and product name, determine that based on other data the product identifier is more likely wrong than the name, and suggest a corrected identifier. In many cases, especially for training data, outliers in data are simply removed from the dataset.

If certain kinds of problems are common, it is possible to write or, more commonly, learn repair rules that can be applied to all past and future data, for example, to always fix the typo “Banananas” to “Bananas.”

Many commercial, academic, and open-source data cleaning tools exist targeted at different communities, such as OpenRefine, Drake, and HoloClean.

Data Linting: Detecting Suspicious Data Encoding

Inspired by static-analysis tools in software engineering (see chapter Quality Assurance Basics), several researchers have developed tools that look for suspicious patterns in datasets, sometimes named data antipatterns or data smells. Problems are detected with heuristics, developed based on experience from past problems. Not every reported problem is an actual problem, but the tool points out suspicious data shapes that may be worth exploring further.

Examples of anti-patterns include suspicious values likely representing missing values like 999 or 1/1/1970, numbers or dates encoded as strings, enums encoded as reals, ambiguous date and time formats, unknown units of measurement, syntactic inconsistencies, and duplicate values. In addition, these tools can find potential problems for data feed into a machine-learning algorithm, such as suggesting normalization of data with many outliers or using buckets or an embedding for zip codes rather than plain numbers

While many assumptions could be codified in a data schema (e.g., types of values in columns, expected distributions for columns, uniqueness of rows), the point of the data linter is to identify suspicious use of data where a schema either has not been defined, or the schema is wrong or too weak for the intended use of the data.

Unfortunately, while there are lists of common problems and several academic prototypes, we are not aware of any broadly adopted data-linting tools.

Drift and Data-Quality Monitoring

A common problem in products with machine-learning components is that data and assumptions about data may change over time. This is described under different notions of drift or dataset shift in the literature. If assumptions about data are not encoded, checked, or monitored, drift may go unnoticed. Drift usually results in the degradation of a model’s prediction accuracy.

All forms of drift tend to degrade model quality over time. If model quality can be monitored in production, this degradation is often visible as a downward trend. Model updates can revert this trend, at least temporarily.

There are several different forms of drift that are worth distinguishing. While the effect of degrading model accuracy is similar for all of them, there are different causes behind them and different strategies for repairing models or data.

Data drift. Data drift, also known as covariate shift or population drift, refers to changes in the distribution of the input data for the model. The typical problem with data drift is that input data differs from training data over time, leading our model to attempt to make predictions for data that is increasingly far from the training distribution. The model may simply have not learned the relevant concepts yet. For example, a model to detect produce in the supermarket's self-checkout system from a camera image reliably detects cucumbers in many forms, but not the new heirloom variety of a local famer that actually looks quite different—here, the model simply has not seen training data for the new shapes of cucumbers.

Data drift can be detected by monitoring the input distributions and how well they align with the distribution of the training data. If the model attempts many out-of-distribution predictions, it may be time to gather additional training data to more accurately represent the new distribution. It is usually not necessary to throw away or relabel old training data, as the relationship between inputs and outputs has not changed—the old cucumbers are still cucumbers even if new cucumbers look differently this season. Old training data may be discarded if the old corresponding input distributions are no longer relevant, for example, if we decide no longer to sell any cucumbers at all.

Concept drift. Concept drift or concept shift refers to changes in the problem or its context over time that lead to changes in the real-world decision boundary for a problem. Concept drift may be best thought of as cases where labels in a training dataset need to be updated since the last training run. In practice, concept drift often occurs because there are hidden factors that influence the expected label for a data point that are not included in the input data. For example, a fad diet may throw off our predicted seasonal pattern for cucumber sales, creating a spike in demand in the winter month—the old model will no longer predict the demand accurately because the underlying relationship between inputs (month) and outputs (expected sales) have changed due to changes in the environment that have not been modeled. We still make predictions for data from the same distributions as previously, but we now expect different outputs for the same inputs than we may have expected a year or two ago. Underlying concepts and related decision boundaries have changed.

Concept drift is particularly common when modeling trends and concepts that can be influenced by adversaries, such as credit-card-fraud detection or intrusion detection, where attackers can intentionally mask bad actions to look like activity that was previously considered harmless.

Monitoring input or output distributions is not sufficient to detect concept drift. Instead, we reason about how frequently predictions were wrong, typically by analyzing telemetry data, as we will discuss in chapter Testing and Experimenting in Production. If the system's prediction accuracy degrades without changes in the input distributions, concept drift is a likely culprit. In this case, the model needs to be updated with more recent training data that captures the changed concept. We need to either relabel old data or replace it with new freshly-labeled training data.

An illustration of the difference between data drift, where distributions change but the real-world decision boundary remains stable, and concept drift, where the decision boundary moves.

Schema drift. Schema drift refers to changes in the data format or assumptions about the meaning of the data. Schema drift typically emerges from technical changes in a different component of a system that produces data. If schema drift is not detected, the data consumer misinterprets the data, resulting in wrong predictions or poor models. For example, a point-of-sale terminal may start recording all weights in kilograms rather than pounds after a software update, leading to misleading values in downstream tasks; this might be visible when reports suddenly show only half the sales volume.

In contrast to data drift and concept drift, which usually occur due to changes in the environment not under our control, schema drift is a technical problem between multiple components that can be addressed with technical means. Schema and encoding changes are always risky when data is communicated across modules or organizations.

Ideally, data exchanged between producers and consumers follows a strict schema, which is versioned and enforced, revealing mismatching versions as a technical error at compile time or runtime. Even if no schema is available from the producer, the data consumer can strictly check assumptions about incoming data as a defensive strategy. This way, the consumer can detect many changes to the format, such as adding or removing columns or changing the type of values in columns. Depending on the repair strategy, the system might report errors when receiving ill-formatted data or just silently drop all incoming ill-formatted data.

A well-specified and automatically checked schema can detect some but not all problems. Semantic changes that modify what values mean, such as the change from pounds to kilogram above, are not automatically detectable. The best approach here is to monitor for changes in documentation and for abrupt changes in data distributions, similar to monitoring data drift.

Monitoring for drift. Proactive monitoring and alerting in production is a common and important strategy to detect drift. To detect data drift, we typically compare the distribution of current inference data (a) to the distribution of training data or (b) to the distribution of past inference data. To detect schema drift, we look for abrupt changes. To detect concept drift, we need access to labels and monitor prediction accuracy over time.

There are many different measures that can be observed. Here, we provide some ideas:

-

Difference between inference data and past or training data distribution: Many measures exist to measure the difference between two distributions, even in high-dimensional spaces. Simple measures might just compute the distance between the means and variance of distributions over time. More sophisticated measures compare entire distributions, such as the Wasserstein distance and KL divergence. Many statistical tests can determine whether two datasets are likely from the same distribution. By breaking down distributions of individual features or subdemographics, it may be possible to understand what part of the data drifts.

-

Number of outliers or low-confidence predictions: The number of inference data points far away from the training distribution can be quantified in many ways. For example, we can use an existing outlier detection technique, use a distance measure to identify the distance to the nearest training data point, and use the confidence scores of the model as a proxy. An increase in outliers in inference data suggests data drift.

-

Difference in influential features and feature importance: Various explainability techniques can identify what features are important for a prediction or which features a model generally relies on the most, as we will discuss in chapter Explainability. We can use distribution difference measures to see whether the model starts relying on different features for most of its predictions or whether models trained on different periods of data (assuming we have labels) rely on different features.

-

Number of ill-formatted inputs or repairs: If ill-formatted inputs are dropped, it is worth recording them to see a sudden rise as indicative of schema drift. If missing values or other data-quality problems are repaired automatically, it is again worth tracking how many repairs are made.

-

Number of wrong predictions: If the correctness of a prediction can be determined or approximated from telemetry data, observing any accuracy measure over time can provide insights into the impact of all forms of drift.

These days, some commercial and open source tools exist that provide sophisticated techniques for data monitoring and drift detection out of the box, such as Evidently, and most platforms provide tutorials on how to set up custom data monitoring in their infrastructure. The practical difficulty for monitoring drift is often in identifying thresholds for alerting—how big of a change and how rapid of a change is needed to involve a human.

Coping with drift. The most common strategy to cope with drift is periodically retraining the model on new, more recent training data. If concept drift is involved, we may need to discard or relabel old training data. The point for retraining can potentially be determined by observing when the model's prediction accuracy in production falls below a certain threshold.

If drift can be anticipated, preparing for it within the machine-learning pipeline may be possible. For example, if we can anticipate data drift, we may be able to proactively gather training data for inputs that are less common now but are expected to be more common in the future. For example, we could proactively include pictures of heirloom varieties of different vegetables in our training data now even though we do not sell them yet. We may be able to simulate anticipated changes to augment training data. For example, we can anticipate degrading camera quality when taking pictures of produce at checkout and add artificially blurred versions of the training data during training. If we can anticipate concept drift, we may be able to encode more context as features for the model. For example, we could add a feature on whether the (anticipated) cucumber fad diet is currently popular or whether we are expecting strong variability in sales due to a winter-storm warning.

Data Quality is a System-Wide Concern

In a traditional machine-learning project or competition, data-quality discussions often center on data-cleaning activities, where data scientists understand and massage provided data to remove outliers and inconsistencies, impute missing data, and otherwise prepare data for model training. When building products, we again have much broader concerns—we usually can shape what and how data is collected, we deal with new data continuously and not just an initial snapshot, we work across multiple teams who may have different understandings of the data, we handle data from many different origins with different levels of control and trust, and we often deal with data at massive scale.

Data Quality at the Source

Not surprisingly, there is usually much more leverage in improving the process that generates the data than in cleaning data after it has been collected. In contrast to course projects and data-science competitions, developers of real-world projects often do not just work with provided fixed datasets, but have influence over how data is collected initially and how it is labeled (if needed). For example, a 2019 study reported that 65 percent of all studied teams at a big tech company had some control over data collection and curation.

Depending on the project, influencing data collection can take many shapes: (1) If data is collected manually by workers in the field, such as supermarket employees manually updating inventory numbers or nurses recording health data, developers can usually define or influence data collection procedures, provide and shape forms or electronic interfaces for data entry, and may even have a say in how to design incentive structures for workers to enter high-quality data. (2) If data is collected automatically from sensors or from telemetry of a running system, such as recording sales or tracking with cameras where shoppers spend the most time, we usually have the flexibility of what data to record in what format or how to operationalize measures from raw sensor inputs. (3) If data labeling is delegated to experts or crowd-workers, we can usually define the explicit task given to the workers, the training materials provided, the working conditions and compensation, and whether to collect multiple independent labels for the same data to increase confidence. Even if data collection is outsourced, we can often influence standards and expectations, though some negotiation may be required.

There is a vast amount of literature on the ethics and politics of data, much of which focuses on the often poor conditions of workers who do the majority of data collection and data labeling work. Workers performing data collection, data entry, data labeling, and data cleaning are often poorly compensated, especially in contrast to highly paid data scientists. Often, these workers are asked to perform data-entry work in addition to their existing responsibilities, without additional compensation or relief and without benefiting from the product for which the data will be used. In some cases, the product for which data is collected may even threaten to replace their jobs. When data quality is poor, it is easy to blame the data workers as non-compliant, lazy, or corrupt and increase surveillance of data workers as a response, rather than reflecting on how the system design shapes data collection incentives and practices. Deliberate design of how data is collected can improve data quality directly at the source.

Usually, field workers collecting data, whether supermarket employees or nurses, have valuable expertise for understanding the context of data, detecting mistakes in data, and understanding patterns. Data scientists using that data are often removed from that domain knowledge and consider the data in a more abstract and idealized form. Projects usually benefit from a closer collaboration of the producers and the consumers of the data in understanding quality issues, from collaboratively setting quality goals, and from providing an environment where high-quality data can be collected.

Data Documentation

Data often moves across organizational boundaries, where those producing the data are often not in direct contact with those consuming the data. As with other forms of documentation at the interface between components and teams (e.g., model documentation discussed in chapter Deploying a Model), documenting data is important to foster coordination but is often neglected.

Data-schema specifications and some textual documentation of the meaning of data can provide a basic description of data and allows a basic form of integrity checking. More advanced approaches for data documentation describe the intention or purpose of the data, the provenance of the data, the process of how the data was collected, and the steps taken to assure data quality. We can also document distributions of the data and subpopulations, known limitations, and known biases.

Several proposals exist for specific formats to document datasets, often focused on publicly shared datasets, such as those used for benchmark problems in machine-learning research. For example, the datasheets for datasets template comprehensively asks 57 questions about motivation, composition, preprocessing and labeling, uses, distribution, and maintenance. Many of these documentation templates focus on proactively describing aspects that could lead to ethical concerns, such as biased operationalization or sampling of the data, possible conflicts of interest, and unintended use cases.

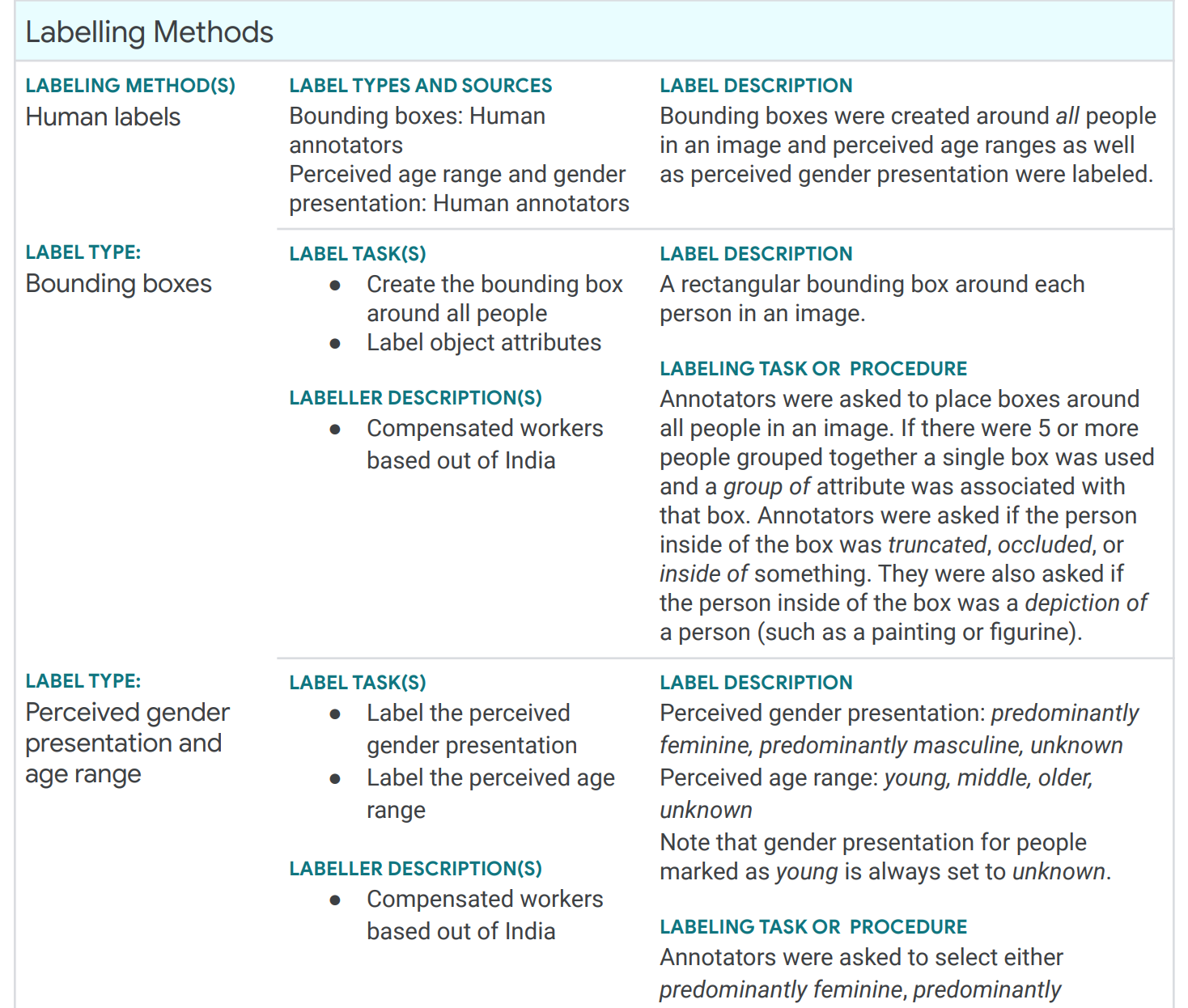

An excerpt from a “Data Card” for Google’s Open Images Extended dataset (full data card) describing the data collection and labeling process, distributions of the data, and anticipated possible biases.

In addition, several data catalog systems and metadata platforms, such as DataHub, ODD, and OpenMetadata, have been developed to index, document, and discover datasets within an organization or even as a public marketplace for datasets. Similar to feature stores indexing reusable features in an organization (see chapter Deploying a Model), a data catalog provides a searchable index of known datasets, ideally with attached schemas and documentation. These tools typically integrate with monitoring and data-quality checking facilities, too.

Data Provenance, Data Archival, and Data Privacy

In addition to concerns about the quality of the form and meaning of data, there are also many quality concerns about how data is stored and processed. We discuss most of these issues in different chapters.

Data provenance (and data lineage) refers to tracking the origin of data and who has made what modifications. For example, we may track which employee has entered the received shipment into the system, who has subsequently made a correction, and which data-cleaning code has imputed missing data and where. Tracking data provenance can build trust in data and facilitate debugging. In addition, data versioning allows us to track how data has changed over time and restore past data. We will cover these topics in more detail in chapter Versioning, Provenance, and Reproducibility.

Secure and archival long-term data storage can ensure that data remains available and private. Redundant storage and backups can protect from data loss due to hardware failures, and standard security practices such as authentication and encryption can prevent unauthorized access. For example, we would not want to lose past sales data irrevocably when a developer accidentally deletes the wrong table, and we do not want to leak customer data on the internet. Database systems and cloud-data-storage solutions specialize in reliable storage and usually provide sophisticated security features and facilities for backups and redundancy.

Scalable storage and processing becomes a quality concern if we amass very large datasets. For example, the total sales data from a supermarket chain might quickly exceed the storage capacity of a single hard drive and the processing capacity of a single machine. Fortunately, plenty of infrastructure exists for scaling data storage and data processing, as discussed in chapter Scaling the System.

When we collect and process personal data, data privacy becomes a concern, one where legal compliance becomes important in many jurisdictions. To ensure privacy, we can use traditional security features to protect stored data against unauthorized access, but developers should also consider what data is needed in the first place and whether data can be anonymized. We will discuss this concern in chapter Security and Privacy.

Most of these quality concerns are addressed through infrastructure in the entire system, often at the level of database systems and big-data processing systems. An organization can provide a solid infrastructure foundation on which all teams can build. While the infrastructure comes with some complexity, especially compared to experimenting with files in a notebook on a local machine, it can provide many benefits for consistent data handling that can positively influence many aspects of data quality, including credibility, currentness, confidentiality, recoverability, compliance, portability, and traceability.

Data-Quality Management

Data quality can be planned and managed in a project. Ideally, data-quality requirements are established early in a project, and those requirements are documented and communicated clearly across team boundaries. Then, data quality should be checked, measured, and continuously monitored according to those requirements.

In practice, requirements and documentation are often not explicit. Given the iterative nature of data-science projects (see chapter Data Science and Software Engineering Process Models), it is often difficult to establish quality requirements early on, as substantial experimentation and iteration may be needed to identify what data is needed and can be acquired at feasible cost and quality. However, once a project stabilizes, it is worth revisiting the data-collection process, defining and documenting data-quality expectations, and setting up a testing and monitoring infrastructure. Standards for data-quality models, such as ISO/IEC 25012, may be used as a checklist to ensure that all relevant notions of data quality are identified and checked.

More broadly, several frameworks for data-quality management exist, such as TDQM and ISO 8000-61, most of which originate from business initiatives for collecting high-quality data for strategic decision-making in a pre-machine-learning era. Those management frameworks focus on aligning quality requirements with business goals, assigning clear responsibilities for data-quality work, establishing a monitoring and compliance framework, and establishing organization-wide data-quality standards and data-management infrastructure. For example, an organization could (1) assign the task of creating regular data-quality reports to one of the team members, (2) hold regular team meetings to discuss these reports and directions for improvement, (3) hire experts that conduct audits for compliance with data-privacy standards, and (4) could build all data infrastructure on a platform that has built-in data versioning and data-lineage-tracking capabilities. While a data-quality-management framework might add bureaucracy and cost, it can ensure that data quality is taken seriously as a priority in the organization.

Summary

Data and data quality are obviously important for machine-learning projects. While more data often leads to better models, the quality of that data is equally important, especially as inaccurate data can systematically bias the resulting model.

In production machine-learning systems, data typically comes from many sources and is often inaccurate, imprecise, inconsistent, incomplete, or has other quality problems. Hence, deliberately thinking about and assuring data quality is important. A first step is usually understanding the data and possible problems, where classic exploratory data analysis is a good starting point. To detect data-quality problems and clean data, there are many different techniques. Most importantly, data schemas ensure format consistency and can encode rules to ensure integrity across columns and rows. Beyond schema enforcement, many anomaly detection techniques can help to identify possible inconsistencies in the data. We also expect to see more tools that point out suspicious code and data, such as the data linter.

Beyond assuring the quality of the existing data, it is also important to anticipate changes and monitor data quality over time. Different forms of drift can all reflect changes in the environment over time that result in degraded prediction accuracy for a model. Planning for drift, preparing to regularly retrain models, and monitoring for indicators of drift in production are important to confidently operate a machine-learning system in production.

Finally, data quality cannot be limited to analyzing provided datasets. Many quality problems are rooted in problems how data was initially collected and in poor communication across teams. For example, separating those producing the data from those consuming the data, without a deliberate design of the data collection process and without proper documentation of data, often leads to bad assumptions and poor models. Deliberately designing the data-collection process provides high leverage for improving data quality. Data quality must be considered as a system-wide concern that can be proactively managed.

Further Readings

-

General articles and books on data quality and data cleaning: 🗎 Rahm, Erhard, and Hong Hai Do. “Data Cleaning: Problems and Current Approaches.” IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 23.4, 2000: 3–13. 🕮 Ilyas, Ihab F., and Xu Chu. Data Cleaning. Morgan & Claypool, 2019. 🕮 Moses, Barr, Lior Gavish, and Molly Vorwerck. Data Quality Fundamentals. O'Reilly, 2022. 🕮 King, Tim, and Julian Schwarzenbach. Managing Data Quality: A Practical Guide. BCS Publishing, 2020.

-

An excellent introduction to common practical data-quality problems in ML projects and how they are deeply embedded in practices and teams, as well as a good overview of existing literature on the politics of data and data-quality interventions: 🗎 Sambasivan, Nithya, Shivani Kapania, Hannah Highfill, Diana Akrong, Praveen Paritosh, and Lora M. Aroyo. “‘Everyone Wants to Do the Model Work, Not the Data Work’: Data Cascades in High-Stakes AI.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), 2021.

-

A follow-up paper that further explores the often fraught relationship between producers and users of data and how they result in data-quality issues: 🗎 Sambasivan, Nithya, and Rajesh Veeraraghavan. “The Deskilling of Domain Expertise in AI Development.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), 2022.

-

An essay about the value and underappreciation often associated with data-collection and data-quality work: 🗎 Møller, Naja Holten, Claus Bossen, Kathleen H. Pine, Trine Rask Nielsen, and Gina Neff. “Who Does the Work of Data?” Interactions 27, no. 3 (2020): 52-55.

-

A collection of articles illustrating the many decisions that go into data collection and data representation, illustrating how data is always an abstraction of the real-world phenomenon it represents and can never be considered “raw:” 🕮 Gitelman, Lisa, ed. Raw Data Is an Oxymoron. MIT Press, 2013.

-

An illustration of the power inherent in defining what data to collect and how to collect it: 🗎 Pine, Kathleen H., and Max Liboiron. “The politics of measurement and action.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), pp. 3147-3156. 2015.

-

Descriptions of the data-quality infrastructure at Amazon and Google, with a focus on efficient schema validation at scale and schema inference: 🗎 Schelter, Sebastian, Dustin Lange, Philipp Schmidt, Meltem Celikel, Felix Biessmann, and Andreas Grafberger. “Automating Large-Scale Data Quality Verification.” Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 11, no. 12 (2018): 1781–1794. 🗎 Polyzotis, Neoklis, Martin Zinkevich, Sudip Roy, Eric Breck, and Steven Whang. “Data Validation for Machine Learning.” Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 1 (2019): 334–347.

-

Short tutorial notes providing a good overview of relevant work in the database community: 🗎 Polyzotis, Neoklis, Sudip Roy, Steven Euijong Whang, and Martin Zinkevich. 2017. “Data Management Challenges in Production Machine Learning.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management of Data, pp. 1723–1726. ACM.

-

Using machine-learning ideas to identify likely data-quality problems and repair them: 🗎 Theo Rekatsinas, Ihab Ilyas, and Chris Ré, “HoloClean - Weakly Supervised Data Repairing.” [blog post], 2017.

-

A great overview of anomaly detection approaches in general: 🗎 Chandola, Varun, Arindam Banerjee, and Vipin Kumar. “Anomaly Detection: A Survey.” ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 41, no. 3 (2009): 1–58.

-

A formal statistical characterization of different notions of drift: 🗎 Moreno-Torres, Jose G., Troy Raeder, Rocío Alaiz-Rodríguez, Nitesh V. Chawla, and Francisco Herrera. “A Unifying View on Dataset Shift in Classification.” Pattern Recognition 45, no. 1 (2012): 521–530.

-

A discussion of data-quality requirements for machine-learning projects: 🗎 Vogelsang, Andreas, and Markus Borg. “Requirements Engineering for Machine Learning: Perspectives from Data Scientists.” In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Requirements Engineering (AIRE), 2019.

-

An empirical study of deep-learning problems highlighting the important role of data quality: 🗎 Humbatova, Nargiz, Gunel Jahangirova, Gabriele Bavota, Vincenzo Riccio, Andrea Stocco, and Paolo Tonella. “Taxonomy of Real Faults in Deep Learning Systems.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Engineering, 2020, pp. 1110–1121.

-

An entire book dedicated to monitoring data quality, including detecting outliers and setting up effective alerting strategies: 🕮 Stanley, Jeremy, and Paige Schwartz. Automating Data Quality Monitoring at Scale. O'Reilly, 2023

-

Many proposals for documentation of datasets: 🗎 Gebru, Timnit, Jamie Morgenstern, Briana Vecchione, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan, Hanna Wallach, Hal Daumé Iii, and Kate Crawford. “Datasheets for Datasets.” Communications of the ACM 64, no. 12 (2021): 86–92. 🗎 Holland, Sarah, Ahmed Hosny, Sarah Newman, Joshua Joseph, and Kasia Chmielinski. “The Dataset Nutrition Label.” Data Protection and Privacy 12, no. 12 (2020): 1. 🗎 Bender, Emily M., and Batya Friedman. “Data Statements for Natural Language Processing: Toward Mitigating System Bias and Enabling Better Science.” Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 6 (2018): 587–604.

-

A controlled experiment that showed that documentation of datasets can positively facilitate ethical considerations in ML projects: 🗎 Boyd, Karen L. “Datasheets for Datasets Help ML Engineers Notice and Understand Ethical Issues in Training Data.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5, no. CSCW2 (2021): 1–27.

-

Catalogs of data-quality problems that can be identified as smells and potentially detected with tools: 🗎 Nick Hynes, D. Sculley, Michael Terry. “The Data Linter: Lightweight Automated Sanity Checking for ML Data Sets.” NIPS Workshop on ML Systems (2017). 🗎 Foidl, Harald, Michael Felderer, and Rudolf Ramler. “Data Smells: Categories, Causes and Consequences, and Detection of Suspicious Data in AI-Based Systems.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI Engineering: Software Engineering for AI, 2022, pp. 229–239. 🗎 Shome, Arumoy, Luis Cruz, and Arie Van Deursen. “Data Smells in Public Datasets.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI Engineering: Software Engineering for AI, 2022, pp. 205-216.

-

A study at a big tech company about fairness, that among others identifies that many teams have substantial influence over what data gets collected: Holstein, Kenneth, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan, Hal Daumé III, Miro Dudik, and Hanna Wallach. “Improving Fairness in Machine Learning Systems: What Do Industry Practitioners Need?” In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), 2019.

As all chapters, this text is released under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. Last updated on 2024-06-17.