Technical Debt

Technical debt is a powerful metaphor for trading off short-term benefits with later repair costs or long-term maintenance costs. Just like taking out a loan provides the borrower with money that can be used immediately but needs to be repaid later with accumulated interest, in the software development analogy, certain actions provide short-term benefits, such as more features and earlier releases, but come at the cost of lower productivity, needed rework, or additional operating costs later—the common Dagstuhl 16162 definition hence describes technical debt as “design or implementation constructs that are expedient in the short term, but set up a technical context that can make a future change more costly or impossible.” Just as with financial debt, technical debt can accumulate and suffocate a project when it becomes no longer possible to productively continue to develop and maintain a system due to old decisions that would have to be fixed first.

The power of the technical debt metaphor comes from its simplicity and ease of communicating implications with non-developers, including managers and customers. For example, using the debt metaphor, it is easier to explain why developers want to spend time on infrastructure and maintenance work now rather than spending all their time on completing features, because it conveys the dangers of delaying infrastructure and maintenance work and the delayed costs of using shortcuts in development. In short, “technical debt” is management-compatible language for software developers.

Technical debt comic by Cornel [Online-only figure.]

Scenario: Automated Delivery Robots

As a running example, consider autonomous delivery robots, which are currently deployed on sidewalks in many college campuses and some cities. Typically the size of a small suitcase, these robots bring food deliveries from restaurants to homes within an area. Based on camera inputs and GPS location, they navigate largely autonomously on sidewalks, which they share with pedestrians. Human operators can take over and navigate the robot remotely if problems occur. Sidewalk robots can have much larger capacities and range than aerial drones.

(Kiwibot, CC-BY-SA-4.0 by Ganbaruby) [Online-only figure.]

Deliberate and Prudent Technical Debt

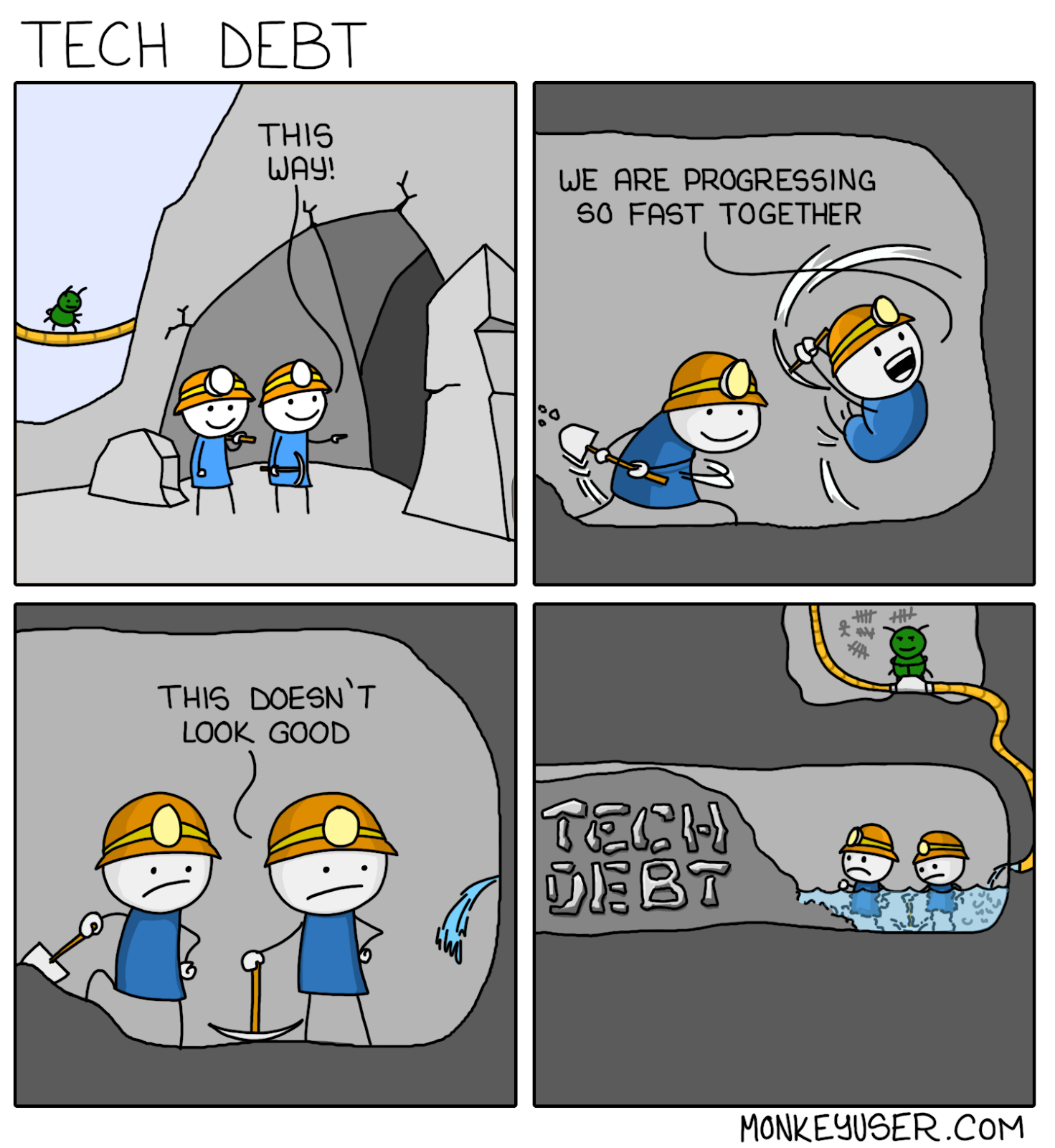

In casual conversations, technical debt is often used to refer to bad decisions in the past that now slow down the project or require rework. However, in a popular blog post, Martin Fowler provides a useful, more nuanced view of different forms of technical debt considering two dimensions:

An illustration of Fowler’s technical debt quadrants for machine-learning projects.

Deliberate versus inadvertent technical debt. Most financial debt comes from a deliberate decision to take out a loan. Also, technical debt can come from deliberate decisions to take a shortcut, knowing that it will cost them later. For example, the developers of the delivery robot may decide to build and deploy an obstacle-detection model in their robots, but rather than investing in an automated pipeline, they just manually copy data, run a notebook, and then copy the model to the robot. They do this despite knowing that it will slow down future updates, make it harder to compare different models or run experiments in production (see chapter Testing and Experimenting in Production), and make it riskier to introduce subtle faults (see chapter Pipeline Quality). They know that they will have to build an automated pipeline eventually and will have to deal with more issues that may arise in the meantime. Still, they make the deliberate decision to prioritize getting a first prototype out now over maintainable infrastructure—that is, they deliberately trade off short-term benefits with later costs.

In contrast, developers may inadvertently make decisions that will incur later costs without thinking through the benefit-cost trade-off. For example, the robot’s data science team may not even be aware of the benefits of pipeline automation and only later realize that their past decisions slow down their current development as they spend hours copying files and remembering which scripts to call every time they want to test a new release. Inadvertent technical debt often comes from not understanding the consequences of engineering decisions or simply not knowing about better practices. Some developers only learn about how they could have built the system better at an earlier stage once they face a problem and explore possible solutions.

Reckless versus prudent technical debt. In the financial setting, many loans are used for investments that provide a chance for high or long-term returns. In the same way, engineering decisions that favor short-term benefits over long-term maintenance costs may be a prudent, good investment. For example, while delivery robots are a new hot market with many competitors, it may be very valuable to have a working prototype and deploy them in many cities to attract investors and customers, so it may be worth deploying many robots early even when the navigation models are still low quality, paying instead heavily for human oversight that will remotely operate the robots in many situations. Similarly, many companies may decide to take shortcuts that incur significant operating and maintenance costs to acquire lots of users quickly in a market with strong network effects where value is made through the size of the user base (e.g., social networks, video conferencing, dating sites, app stores).

However, not all debt is prudent. Credit cards may be used for impulsive spending above a person’s means and lead to high-interest charges and a cycle of debt. Similarly, technical decisions can be reckless, where shortcuts are taken without investing in future success or by causing future costs that will suffocate the project. For example, forgoing safety testing for the delivery robot’s perception models may speed up development, but may cause bad publicity and serious financial liability in case of accidents and may cause cities to revoke the licenses to operate.

Ideally, all technical debt is deliberate and prudent. Ideally, developers consider their options and deliberately decide that certain benefits, such as a faster release, are worth the anticipated future costs. Hopefully, deliberate but reckless decisions are rare in practice. Of course, inadvertent technical debt can also turn out to be prudent—for example, when the low accuracy of early models forced the company to rely heavily on human interventions without anybody ever deliberately choosing that path, this may accidentally turn out as a lucky strategy because it allowed gathering more training data and driving a competitor out of the market. In practice though, many forms of technical debt will be inadvertent and reckless. Not knowing better or being under immense stress to deliver quickly, developers may take massive shortcuts that become very expensive later.

Technical Debt in Machine-Learning Projects

Machine learning makes it very easy to inadvertently accumulate massive amounts of technical debt, especially when inexperienced teams try to deploy products with machine-learning components in production. In a very influential article, originally titled “Machine Learning: The High Interest Credit Card of Technical Debt,” Sculley and other Google engineers describe many ways machine learning projects incur additional forms of maintenance costs beyond that of traditional software projects and frame them as technical debt. Since then, many studies have analyzed and discussed various forms of technical debt in machine-learning projects.

First of all, using machine learning where it is not necessary creates technical debt: using machine learning can seem like a quick and easy solution to a problem, especially when machine learning is hyped in the media and by consultants, but it can come with long term costs that the initial developers may not anticipate. As we discuss throughout this book, engineering production-quality machine-learning components can be expensive and induce long-term maintenance costs. Developers may decide to use machine learning as a gimmick or to solve a problem where heuristics are sufficient or established non-ML solutions exist, not anticipating the costs later—this could be inadvertent, reckless technical debt.

In addition, poor engineering practices in machine-learning projects can introduce substantial technical debt. Throughout this book, we discussed many good engineering practices that reduce maintenance costs and risks, such as hazard analysis and planning for mistakes, system architecture design, building robust pipelines, testing in production, fairness evaluations, threat modeling, and provenance tracking. These practices address emerging problems and are designed to avoid long-term costs, but they all require an up-front investment to perform some analysis or adopt or develop nontrivial infrastructure. Hence, skipping good engineering practices can introduce technical debt. Commonly discussed forms of technical debt include:

-

Data debt: Data introduces many internal and external dependencies on components that produce and process the data. For example, our robot’s navigation software may rely on map data and weather data provided by third parties, on labeled obstacle-recognition training data from other researchers, and on camera inputs from hopefully well-maintained and not-tempered cameras on the robot. The quality and quantity of data on which a machine-learning project depends may change over time, and without checking and monitoring of data quality, such as creating a schema for the data, monitoring for distribution shift, and tracking the provenance of data, such issues might go unnoticed until customer complains mount (see chapter Data Quality).

-

Infrastructure debt: It is easy to develop models with powerful libraries in a notebook and to copy the resulting model into a production system, but without investment in automation the process can be brittle and tedious (see chapter Automating the Pipeline). For example, without a solid deployment step, we may be hesitant to update robots more than once a month due to all the manual effort involved, and we may run the robots on old and inconsistent versions of the models because we did not notice that the update process failed on some of them.

-

Versioning debt: Ad hoc exploratory development in notebooks can also make it difficult to reproduce results or identify what has changed in data or training code since the last release when debugging a performance problem. Versioning of machine learning pipelines with all dependences, and especially versioning of data, requires some infrastructure investment (see chapter Versioning, Provenance, and Reproducibility) but can avoid inconsistencies and maintenance and operations emergencies, and enable rapid experimentation in production. For example, without data versioning, we might not be able to track down if any (possibly even malicious) changes in the training data now cause the robot to no longer recognize dogs as obstacles.

-

Observability debt: Evaluating a model offline on a static dataset is easy, but building a monitoring infrastructure to evaluate model quality in production requires nontrivial infrastructure investments early on (see chapter Testing and Experimenting in Production). Without up-front infrastructure investments in monitoring infrastructure, the development team might have little idea of how to fix production problems, and each time they guess and try something, they spend days manually watching a few robots.

-

Code quality debt: Similar to many traditional software projects, machine-learning projects report code quality problems that can make maintenance more difficult, such as delayed code cleanups, code duplication, poor readability, poor code structure, inefficient code, and missing tests. Code maintenance problems are also common in ML-pipeline code, originating, for example, from dead experimental code, glued-together scripts, duplicate implementation of feature extraction, poorly named variables, and a lack of code abstraction in model training code. For example, developers of the delivery robot may have a hard time figuring out all locations where to apply a patch to feature extraction code and which scripts to run in what order to create a new version of a model. The experimental nature of much data-science code can contribute to code quality problems unless the team explicitly invests in cleanup when the pipeline is ready to be released (see chapter Pipeline Quality).

-

Architectural debt and test debt: It is easy to build products that use multiple machine-learned models and have some models consume outputs of other models. However, it is difficult to separate the effects of these models in a project without investing in model testing and integration testing (see chapter System Quality). Without this, developers might only guess which of the five recently updated models in the robot causes the recent tendency to navigate into bike lanes.

-

Requirements debt: Careful requirements analysis can help to detect potential feedback loops and design interventions as part of the system design, before they become harmful (see chapter Gathering Requirements); skipping such analysis may lead to feedback loops manifesting in production that cause damage and are harder to fix later, including serious ethical and safety implication with long-term harms. For example, a delivery robot optimized for speedy delivery times may adopt risky driving behavior, causing pedestrians to mostly evade the robot, leading to even higher speeds and positive reinforcement for faster deliveries, but less safe neighborhoods.

In a way, all these discussed forms of technical debts characterize the long-term problems that may occur when skipping investment in responsible engineering practices. It can be prudent to skip up-front engineering steps to build a prototype fast, but projects should consider paying back the debt to avoid continuous high maintenance costs and risks. Arguing for good engineering practices through the lens of technical debt may help convince engineers and managers why they should invest in requirements analysis, systematic testing, online monitoring, and other good engineering practices—for example, by hiring more team members or prioritizing design and infrastructure improvements over developing new features.

Managing Technical Debt

Technical debt is not an inherently bad thing that needs to be avoided at all cost, but ideally, taking on technical debt should be a deliberate decision. Rather than inadvertently omitting data quality tests or monitoring, teams should consider the potential long-term costs of these decisions and deliberately decide whether skipping or delaying such infrastructure investment is worth the short-term benefit, such as moving faster toward a first release. Of course, to make deliberate decisions about technical debt, teams must know about good practices and state-of-the-art tools in the first place.

Not all technical debt can be repaid equally easily. For example, skipping risk analysis up-front may lead to a fundamentally flawed system design that will be hard to fix later: we may realize only after ordering thousands of units that our robots really should have been constructed with redundant sensors. Other delayed actions may be easier to fix later: for example, if we do not build a monitoring infrastructure today, we have little visibility into how the model performs, but we can add such infrastructure later without redesigning the entire system. Generally, requirements-related and design-related technical debt is usually much harder to fix than technical debt related to low code quality and a lack of automation.

In many cases, inadvertent technical debt can be avoided through education or by making it easier to do the right thing. For example, if using version control is part of the team culture, new team members are less likely to acquire versioning debt. Similarly, if risk analysis is a normal part of the process or team members regularly ask questions about fairness in meetings, engineers are less likely to skip those steps without a good reason. Especially in more mature organizations, it may be easier to provide or even mandate a uniform infrastructure that automates important steps or prevents certain shortcuts, such as ensuring that all machine learning is conducted in a managed infrastructure that automatically versions data, tracks data dependencies, and tracks provenance (see chapter Versioning, Provenance, and Reproducibility).

If a team deliberately decides to take on technical debt, the debt should be managed. At a minimum, the necessary later infrastructure and maintenance work should be tracked in an issue tracker. For example, when skipping to build a robust pipeline, it is a good idea to add a reminder to invest in a robust pipeline as a todo item for later, either as a short-term entry in a product backlog or as a long-term strategic plan in a product roadmap. Ideally, responsibility for technical debt from a decision assigned to a specific person, the extra maintenance cost incurred is monitored, and specific goals are set for whether and when to pay it back. Some organizations adopt “fix-it” days or weeks where engineers interrupt their usual work to focus on addressing a backlog of technical debt.

Teams will never be able to fully resolve the tension between releasing products quickly and implementing more features on the one hand and focusing on design and infrastructure and long-term maintainability on the other hand. However, the technical-debt metaphor gives teams the vocabulary to push for better practices, for time to do cleanup and maintenance, and for investment in infrastructure.

Summary

Technical debt is a good metaphor to communicate the idea of taking shortcuts for some short-term benefits, such as a faster release, at the cost of lower productivity later or higher long-term maintenance costs. Ideally, taking on technical debt is a deliberate and prudent decision with debt then managed and actively repaid. In practice though, technical debt can often occur inadvertently and recklessly, often through inexperience or external pressure.

Machine learning brings many additional challenges that can easily result in high long-term maintenance costs if not addressed aggressively through good engineering practices for requirements, design, infrastructure, and automation, as discussed throughout this book. It is easy to build and deploy a machine-learned model in a quick-and-dirty fashion, but it may require significant engineering effort to build a maintainable production system that can be operated with reasonable cost and confidence. Delaying design, infrastructure, and automation investment might be prudent but should be considered deliberately rather than out of ignorance. If deciding to delay such important work, it is a good idea to track the resulting technical debt and ensure that time is allocated to pay it back eventually.

Further Readings

-

This early paper on engineering challenges of ML systems framed as technical debt was extremely influential and is often seen as a focal motivation for the MLOps movement: 🗎 Sculley, David, Gary Holt, Daniel Golovin, Eugene Davydov, Todd Phillips, Dietmar Ebner, Vinay Chaudhary, Michael Young, Jean-Francois Crespo, and Dan Dennison. “Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 2503–2511. 2015.

-

Several subsequent research studies have explored technical debt in ML libraries and data science projects, often by studying TODO comments in source code as self-admitted technical debt: 🗎 OBrien, David, Sumon Biswas, Sayem Imtiaz, Rabe Abdalkareem, Emad Shihab, and Hridesh Rajan. “23 Shades of Self-Admitted Technical Debt: An Empirical Study on Machine Learning Software.” In Proceedings of the Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, pp. 734–746. 2022. 🗎 Tang, Yiming, Raffi Khatchadourian, Mehdi Bagherzadeh, Rhia Singh, Ajani Stewart, and Anita Raja. “An Empirical Study of Refactorings and Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems.” In International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), IEEE, 2021, pp. 238–250. 🗎 Alahdab, Mohannad, and Gül Çalıklı. “Empirical Analysis of Hidden Technical Debt Patterns in Machine Learning Software.” In International Conference on Product-Focused Software Process Improvement (PROFES), Springer, 2019, pp. 195–202.

-

A good general overview and summary of the literature on technical debt in machine learning systems: 🗎 Bogner, Justus, Roberto Verdecchia, and Ilias Gerostathopoulos. “Characterizing Technical Debt and Antipatterns in AI-Based Systems: A Systematic Mapping Study.” In International Conference on Technical Debt (TechDebt), pp. 64–73. IEEE, 2021.

-

An influential discussion of the dimensions of technical debt as deliberate vs inadvertent and reckless vs prudent: 📰 Fowler, Martin. “Technical Debt Quadrant” [blog post], 2019.

-

A book covering technical debt and its management broadly: 🕮 Kruchten, Philippe, Robert Nord, and Ipek Ozkaya. Managing Technical Debt: Reducing Friction in Software Development. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2019.

-

A commonly used definition for technical debt originates from the Dagstuhl 16162 meeting: 🕮 Avgeriou, Paris, Philippe Kruchten, Ipek Ozkaya, and Carolyn Seaman. “Managing Technical Debt in Software Engineering (Dagstuhl Seminar 16162),” in Dagstuhl Reports, vol. 6, Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, 2016.

As all chapters, this text is released under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. Last updated on 2024-06-10.